- Home

- Letter to President Obama

- Acknowledgements

- Executive Summary

- Preface

- Part 1: The Case for HPV Vaccination

- Part 2: Urgency for Action

- Part 3: Accelerating HPV Vaccine Uptake in the U.S.

- Part 4: Increasing Global HPV Vaccination

- Goal 4: Promote Global HPV Vaccine Uptake

- Part 5: High-Priority Research

- Conclusions

- Appendices

- Acronyms

PART 4

INCREASING GLOBAL HPV VACCINATION*

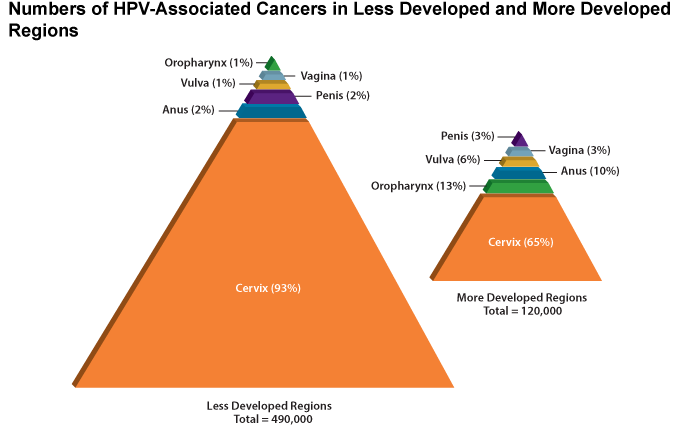

The burden of HPV-associated cancers extends beyond the borders of the United States, affecting populations in every country. Patterns of HPV-associated cancers differ by region. Cervical cancer is the most common HPV-associated cancer globally. In the United States and other more developed regions, other sites account for a significant proportion of HPV-associated cancers (Figure 8). In contrast, in less developed regions, more than 90 percent of HPV-attributed cancers are cervical cancers.[1]

Figure 8

Note: Global estimates of genital warts and RRP incidence are not available.

Source: de Martel C, Ferlay J, Franceschi S, Vignat J, Bray F, Forman D, et al. Global burden of cancers attributable to infections in 2008: a review and synthetic analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(6):607-15. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22575588

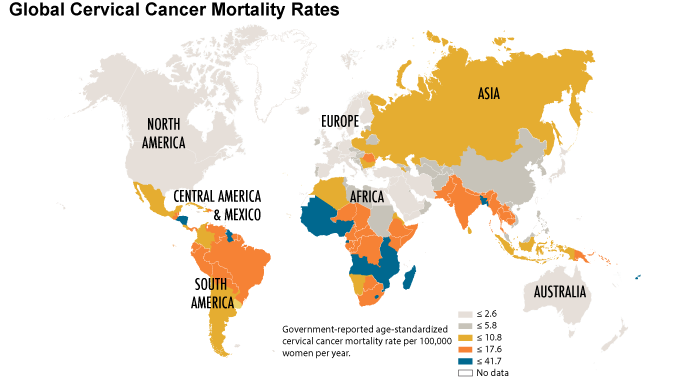

Figure 9 illustrates the uneven burden of cervical cancer across the world, with mortality rates in some parts of Africa being 15 times higher than in North America.[2] These disparities stem, in part, from the fact that the United States and other high-income countries have widespread cervical cancer screening programs and treat precursor lesions and early invasive cervical cancers, dramatically reducing the numbers of new cases and deaths. The absence of such services in many lower-income, less developed countries has resulted in cervical cancer being a leading cause of cancer-related death among women.[2] While the prevalence of HPV infections and distribution of HPV types vary by region, research has found consistently that HPV16 and HPV18, the cancer-causing strains that HPV vaccines protect against, are responsible for at least two-thirds of cervical cancer cases in populations around the world.[3,4] This fact provides a strong indication that HPV vaccines will be effective virtually everywhere. Delaying implementation of HPV vaccine programs will result in missed opportunities to prevent HPV infections responsible for more than 400,000 cancers each year.

Figure 9

Modified from: Crow, JM. HPV: the global burden. Nature. 2012;488:S2-3. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22932437. Data from: World Health Organization, Institut Catala d'Oncologia. Human papillomavirus and related cancers: summary report update. Barcelona (ES): WHO/ICO; 2010 Nov 15.

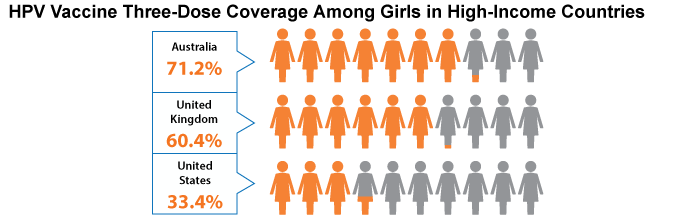

As with cervical cancer screening programs, HPV vaccination programs have been implemented primarily in high-resource areas. Australia, the United Kingdom, and parts of Canada have launched highly effective programs that have achieved higher HPV vaccine uptake than the United States (Figure 10).[5-8] Australia, the U.K., and Canada have national healthcare programs that differ significantly from the healthcare delivery system in the United States, which includes many payers. Nonetheless, the U.S. can learn from successful HPV vaccination programs in other countries, which, in some cases, already have led to measurable public health benefits.[9,10]

Figure 10

Note: National data on HPV vaccine coverage in Canada are not available. However, Canadian provinces report three-dose coverage among target age groups between 50 and 85 percent.

Sources: Australia (girls turning 15 in 2011): Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. Human papillomavirus (HPV) [Internet]. Woden (AU): the Department; [updated 2013 Feb 14; cited 2013 Aug 16]. Available from: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/immunise/publishing.nsf/Content/immunise-hpv; United Kingdom (12- to 19-year-old girls): Sheridan A, White J. Annual HPV vaccine coverage in England in 2009/2010. London (UK): Health Protection Agency, UK; 2010 Dec 22. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/215800/dh_123826.pdf; United States (13- to 17-year-old girls): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Human papillomavirus vaccination coverage among adolescent girls, 2007-2012, and postlicensure vaccine safety monitoring, 2006-2013—United States. MMWR. 2013;62(29):591-5. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23884346; Canada: Saraiya M, Steben M, Watson M, Markowitz L. Evolution of cervical cancer screening and prevention in United States and Canada: implications for public health practitioners and clinicians. Prev Med. 2013;57(5):426-33. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23402963

Addressing the global burden of HPV-associated cancers requires implementation of HPV vaccination programs in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where the majority of HPV-associated cancer cases occur. LMICs face a number of barriers, including limited financial resources, inadequate healthcare delivery systems, and, in some instances, expertise gaps in program planning and implementation.[11] The United States should collaborate with global organizations and LMICs to support efforts to plan and implement HPV vaccination programs in these countries. Learning should be bidirectional; the U.S. can learn from what is accomplished in other countries.

Efforts to introduce and expand HPV vaccination in LMICs are gaining momentum through efforts of the GAVI Alliance (formerly the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunisation) and the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) Revolving Fund. The GAVI Alliance is a public-private partnership focused on increasing access to immunization in poor countries. In 2013, GAVI launched a demonstration program that will provide HPV vaccines to more than 180,000 girls in eight countries.[12] The demonstration programs are designed to give each country the opportunity to test its ability to establish systems needed to implement a national HPV vaccination program (e.g., medical staff, supplies, distribution systems, supply management). GAVI also is supporting implementation of a nationwide HPV vaccination program in Rwanda and partnering with the Islamic Development Bank (IDB) to accelerate the introduction of life-saving vaccines, including HPV, in IDB member countries.[13,14]

In June 2013, GAVI announced successful negotiation for a sustainable supply of HPV vaccine for use in developing countries at an unprecedented low price of $4.50 per dose for Gardasil® and $4.60 per dose for Cervarix®.[12] The lowest previous public-sector cost was $13 per dose. The goal is that by 2020, 30 million girls in 40 countries get the vaccines at or below these prices.

The PAHO Revolving Fund provides a mechanism for many GAVI-ineligible, middle-income nations in Latin America and the Caribbean to procure HPV vaccines at reduced prices.[15] Revolving Fund Member States pool their resources to purchase vaccines and related supplies at discounted bulk rates. The fund also provides countries a 60-day line of credit for purchases and assists with the logistics of vaccine procurement. As of 2012, four countries had introduced HPV vaccines with PAHO Revolving Fund support.[16]

Footnotes

* The terms "developing countries," "developing world," "developing economies," and "low- and middle (or medium)-income countries (LMICs)" are not entirely synonymous, and definitions vary among international aid agencies. The same is true of the terms "developed countries," "developed world," "developed economies," and "higher-income countries (HICs)." However, many agencies use these terms interchangeably except when describing gradations of overall development that may reflect not only Gross National Income (GNI) but also assessments of sustainable infrastructure, human asset indices (e.g., literacy, nutrition), and economic and environmental vulnerabilities. Thus, countries grouped by income level may have significantly varied levels of development. These differences are important because they may determine countries' eligibility for specific types of assistance.

References

- de Martel C, Ferlay J, Franceschi S, Vignat J, Bray F, Forman D, et al. Global burden of cancers attributable to infections in 2008: a review and synthetic analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(6):607-15. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22575588

- World Health Organization, Institut Catala d'Oncologia. Human papillomavirus and related cancers: summary report update. Barcelona (ES): WHO/ICO; 2010 Nov 15.

- Smith JS, Lindsay L, Hoots B, Keys J, Franceschi S, Winer R, et al. Human papillomavirus type distribution in invasive cervical cancer and high-grade cervical lesions: a meta-analysis update. Int J Cancer. 2007;121(3):621-32. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17405118

- Muñoz N, Bosch FX, Castellsagué X, Díaz M, de Sanjose S, Hammouda D, et al. Against which human papillomavirus types shall we vaccinate and screen? The international perspective. Int J Cancer. 2004;111(2):278-85. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15197783

- Australian Government Department of Health Immunise Australia Program. Human papillomavirus (HPV) [Internet]. Woden (AU): the Department; [updated 2013 Feb 14; cited 2013 Aug 16]. Available from: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/immunise/publishing.nsf/Content/immunise-hpv

- Sheridan A, White J. Annual HPV vaccine coverage in England in 2009/2010. London (UK): Health Protection Agency, UK; 2010 Dec 22. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/147510/dh_123826.pdf.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Human papillomavirus vaccination coverage among adolescent girls, 2007-2012, and postlicensure vaccine safety monitoring, 2006-2013—United States. MMWR. 2013;62(29):591-5. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23884346

- Saraiya M, Steben M, Watson M, Markowitz L. Evolution of cervical cancer screening and prevention in United States and Canada: implications for public health practitioners and clinicians. Prev Med. 2013;57(5):426-33. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23402963

- Tabrizi SN, Brotherton JM, Kaldor JM, Skinner SR, Cummins E, Liu B, et al. Fall in human papillomavirus prevalence following a national vaccination program. J Infect Dis. 2012;206(11):1645-51. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23087430

- Ali H, Donovan B, Wand H, Read TR, Regan DG, Grulich AE, et al. Genital warts in young Australians five years into national human papillomavirus vaccination programme: national surveillance data. BMJ. 2013;346:f2032. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23599298

- President's Cancer Panel. Meeting summary. Global HPV vaccination: opportunities and challenges; 2013 Apr 23-24; Miami, FL. Available from: http://deainfo.nci.nih.gov/advisory/pcp/pcpmeetings.htm

- GAVI Alliance. GAVI funds vaccines to protect girls against cervical cancer [Press Release]. Geneva (CH): GAVI Alliance; 2013 Feb 4 [cited 2013 Jul 31]. Available from: http://www.gavialliance.org/library/news/press-releases/2013/gavi-funds-vaccines-to-protect-girls-against-cervical-cancer/

- GAVI Alliance. Islamic Development Bank partners with GAVI to save children's lives with vaccines [Press Release]. Jeddah (SA): GAVI Alliance; 2013 Mar 11 [cited 2013 Jul 31]. Available from: http://www.gavialliance.org/library/news/press-releases/2013/islamic-development-bank-partners-with-gavi-to-save-children-s-lives-with-vaccines/?goback=.gde_3669887_member_222847350

- GAVI Alliance. Millions of girls in developing countries to be protected against cervical cancer thanks to new HPV vaccine deals [Press Release]. Cape Town (ZA): GAVI Alliance; 2013 May 9 [cited 2013 Jul 31]. Available from: http://www.gavialliance.org/library/news/press-releases/2013/hpv-price-announcement/

- Pan American Health Organization. PAHO Revolving Fund [Internet]. Washington (DC): PAHO; [updated 2011 Aug 2; cited 2013 Nov 6]. Available from: http://www.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=1864&Itemid=2234&lang=en

- Khabbaz R. Influence of HPV vaccine policies and financing on vaccine uptake. Presented at: President's Cancer Panel meeting; 2013 Apr 23-24; Miami, FL. Available from: http://deainfo.nci.nih.gov/advisory/pcp/pcpmeetings.htm