PART 2

URGENCY FOR ACTION

In 2006, the U.S. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommended HPV vaccination for adolescent girls and added a similar recommendation for adolescent boys in 2011 (see sidebar).[1-3]* The HPV vaccine series consists of three doses given over six months. Thus, vaccine uptake is a function of both initiation (getting the first vaccine dose) and completion (getting all three vaccine doses).

HPV VACCINES ARE UNDERUSED IN THE U.S.

The U.S. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommends:

- Routine vaccination of females ages 11 or 12 years with three doses of either Cervarix® or Gardasil®. The vaccination series can be started beginning at age 9 years. Vaccination is recommended for females ages 13 through 26 years who have not been vaccinated previously or who have not completed the three-dose series.

- Routine vaccination of males ages 11 or 12 years with Gardasil® administered as a three-dose series. The vaccination series can be started beginning at age 9 years. Vaccination with Gardasil® is recommended for males ages 13 through 21 years who have not been vaccinated previously or who have not completed the three-dose series. Males ages 22 through 26 years may be vaccinated.

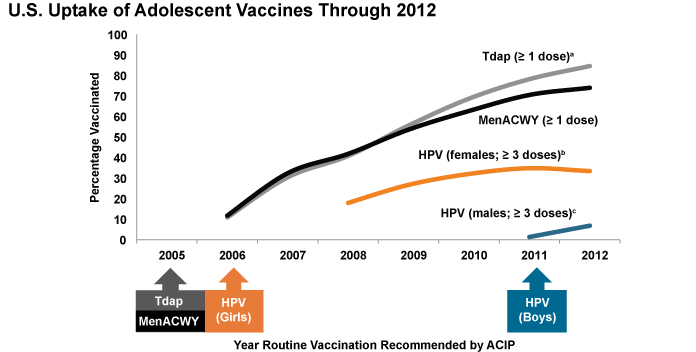

In 2007, the first full year after Gardasil® was approved in the U.S., about one-quarter of 13- to 17-year-old girls received at least one HPV vaccine dose. This is similar to the proportion who received other adolescent vaccines, such as meningococcal conjugate and Tdap vaccines, during the first year they were recommended (Figure 4).[4] However, uptake of HPV vaccines has not kept pace with that of other adolescent vaccines and has stalled in the past few years. In 2012, only 53.8 percent of 13- to 17-year-old girls had received the first HPV vaccine dose, and only 33.4 percent had completed all three recommended doses.[5] These levels are nearly identical to what was observed in 2011 and fall considerably short of the Healthy People 2020 goal of having 80 percent of 13- to 15-year-old girls fully vaccinated against HPV.[6] They also are substantially lower than HPV vaccine coverage rates in other high-income countries, such as Australia and the United Kingdom (U.K.) (see Part 4).

Immunization rates for U.S. boys are even lower than for girls. Only 20.8 percent of boys ages 13-17 had received at least one dose, and only 6.8 percent had completed the series, in 2012.[7] Though only one year after the ACIP recommendation for boys was issued, this rate of HPV vaccine initiation is substantially lower than that observed for girls in 2007, suggesting the need for concerted efforts to promote HPV vaccination of boys.

Figure 4

ACIP = Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; HPV = human papillomavirus; MenACWY = meningococcal conjugate; Tdap = tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis.

a After age 10 years.

b ≥ 3 doses HPV vaccine, either Cervarix® or Gardasil®, among females. ACIP recommends either Cervarix® or Gardasil® for females.

c ≥ 3 doses HPV vaccine, either Cervarix® or Gardasil®, among males. ACIP recommends Gardasil® for males but some males may have received Cervarix®.

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National and state vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13-17 years—United States, 2012. MMWR. 2013 Aug 30;62(34):685-93. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23985496

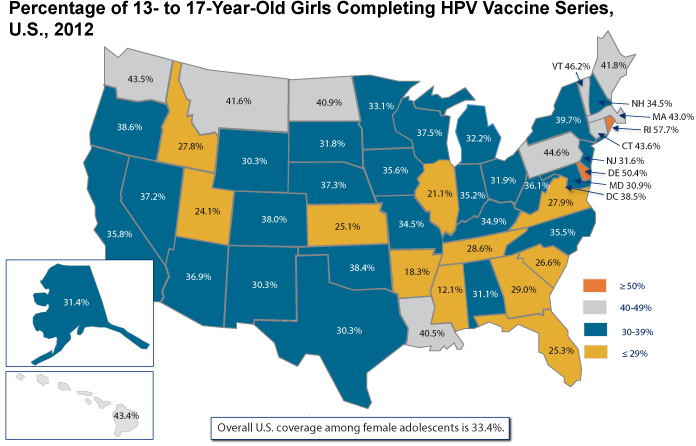

While informative, national HPV vaccination statistics do not reflect regional trends that may be important for HPV-associated cancer prevention efforts. Some states and regions have been more successful than others in achieving uptake of HPV vaccination (Figure 5). As of 2012, more than one-half of girls in only two states (Delaware and Rhode Island) had received the full HPV vaccine series, and vaccine completion was less than 30 percent in 11 states. The lowest rate of HPV vaccine series completion is 12.1 percent.[4] Of particular concern, those states with low rates of HPV vaccine uptake often also have high cervical cancer incidence and mortality rates.[8]†

Figure 5

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National and state vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13-17 years—United States, 2012. MMWR. 2013 Aug 30;62(34):685-93. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23985496. Data from National Immunization Survey-Teen (NIS-Teen) among female adolescents (N = 9,058) born between January 6, 1994, and February 18, 2000. Gardasil® or Cervarix® may have been received; more than the recommended three doses may have been received.

INCREASING HPV VACCINE UPTAKE MUST BE A PUBLIC HEALTH PRIORITY

Concerted, coordinated efforts by multiple public and private organizations are needed to increase HPV vaccine uptake and achieve the vaccines' potential to prevent cancers. These efforts should promote both initiation of the first dose and completion of all three recommended doses for age-eligible adolescents, as well as young adults who have not received HPV vaccines or who have not received all three doses. The opportunity afforded by HPV vaccines to prevent cancers safely and effectively should not be disregarded. CDC estimates that increasing HPV vaccination rates from current levels to 80 percent would prevent an additional 53,000 future cervical cancer cases among girls who now are 12 years old or younger over the course of their lifetimes. This estimate does not include the thousands of U.S. cases of other HPV-associated cancers that likely also would be prevented within the same timeframe. A growing proportion of these cancers—most notably, oropharyngeal cancers—will occur in males, who currently are vaccinated at very low rates. High rates of HPV vaccination have been achieved in other high-income countries and are achievable in the United States through an integrated effort that includes multiple evidence-based strategies.

The following sections of this report include four goals to increase HPV vaccine uptake. Three goals focus on increasing uptake in the United States (Part 3) and the fourth addresses ways the United States can help increase global uptake of the vaccines (Part 4). Several high-priority research areas also are identified (Part 5). Recommendations and some of the stakeholders responsible for implementing them are summarized in Appendix B. The Panel urges all stakeholders—including federal and state governments, healthcare professionals, nongovernment organizations with a focus on public health, and members of the public—to contribute to efforts to achieve this goal and protect millions of men and women around the world from the burden of avoidable cancers and other diseases and conditions in the coming years. Organized, mutually reinforcing efforts could have synergistic impact on HPV vaccine uptake. The Panel views this as an important opportunity to catalyze the prevention of cancer that should not be squandered.

Footnotes

* ACIP issued a permissive recommendation for HPV vaccination of males in 2009. This was upgraded to a routine recommendation in 2011.

† Estimates of incidence and mortality of cervical cancer by state are available on the NCI State Cancer Profiles website: http://statecancerprofiles.cancer.gov/cgi-bin/quickprofiles/profile.pl?00&057#deathMap.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2007;56(RR-2):1-24. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17380109

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. FDA licensure of bivalent human papillomavirus vaccine (HPV2, Cervarix) for use in females and updated HPV vaccination recommendations from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR. 2010;59(20):626-9. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20508593

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations on the use of quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine in males—Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2011. MMWR. 2011;60(50):1705-8. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22189893

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National and state vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13-17 years—United States, 2011. MMWR. 2012;61(34):671-7. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22932301

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Human papillomavirus vaccination coverage among adolescent girls, 2007-2012, and postlicensure vaccine safety monitoring, 2006-2013—United States. MMWR. 2013;62(29):591-5. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23884346

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2020 topics and objectives: immunization and infectious diseases objectives [Internet]. Washington (DC): DHHS; [updated 2013 Apr 24; cited 2013 Jul 26]. Available from: http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/objectiveslist.aspx?topicId=23

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National and state vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13-17 years—United States, 2012. MMWR. 2013;62(34):685-93. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23985496

- Horner MJ, Altekruse SF, Zou Z, Wideroff L, Katki HA, Stinchcomb DG. U.S. geographic distribution of prevaccine era cervical cancer screening, incidence, stage, and mortality. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20(4):591-9. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21266522