- Home

- Letter to President Obama

- Acknowledgements

- Executive Summary

- Preface

- Part 1: The Case for HPV Vaccination

- Part 2: Urgency for Action

- Part 3: Accelerating HPV Vaccine Uptake in the U.S.

- Goal 1: Reduce Missed Clinical Opportunities

- Goal 2: Increase Acceptance of HPV Vaccines

- Goal 3: Maximize Access to HPV Vaccination Services

- Part 4: Increasing Global HPV Vaccination

- Part 5: High-Priority Research

- Conclusions

- Appendices

- Acronyms

Goal 3: Maximize Access to HPV Vaccination Services

The Patient-Centered Medical Home is a care delivery model whereby patients' treatments are coordinated through their primary care physicians to ensure that patients receive necessary and appropriate care when and where they need it, in a manner they can understand.

Source: American College of Physicians.

Several characteristics of service delivery affect vaccine initiation and completion. Vaccines should be available where adolescents receive healthcare. It should be convenient to initiate and complete the HPV vaccine series, and cost should not be a barrier. The Panel encourages adoption of the National Vaccine Advisory Committee Standards for Adult Immunization Practices as a critical component of quality vaccine delivery and administration.[1]

The American Academy of Pediatrics[2] and American Academy of Family Physicians[3] prefer that all adolescents receive primary care, including vaccinations, within a medical home (see sidebar).[4] Medical homes are the optimal environment for administration of HPV vaccines, particularly the first dose, because they provide opportunities to educate parents and adolescents and to deliver other important preventive care services. Reducing missed clinical opportunities for HPV vaccination in physicians' offices and other medical practices will go a long way toward increasing HPV vaccine uptake. However, the Panel recognizes that providing additional venue choices may increase the likelihood that adolescents will receive all three HPV doses. As such, the Panel recommends increasing the range of venues and providers for HPV vaccination.

Many adolescents do not receive regular preventive care through medical homes.

In this way, HPV vaccination would occur within the "medical neighborhood," in venues outside of but in coordination with the medical home. The discussion below focuses especially on pharmacies and raises some issues related to schools.

Objective 3.1: Promote and facilitate HPV vaccination in venues outside the medical home.

Objective 3.2: States should enact laws and implement policies that allow pharmacists to administer vaccines to adolescents, including younger adolescents.

Objective 3.3: Overcome remaining barriers to paying for HPV vaccines, including payment for vaccines provided outside the medical home and by out-of-network or nonphysician providers.

Objective 3.1: Promote and facilitate HPV vaccination in venues outside the medical home.*

While medical homes are the optimal environment for delivery of preventive health services, including vaccinations, many adolescents—particularly males, racial/ethnic minorities, adolescents from low-income families, and older adolescents—do not receive regular preventive care through medical homes.[5-10] Lack of a medical home may affect immunization coverage for all vaccines, but HPV vaccination is likely disproportionately affected, given the number of visits needed to complete the series.[10] The range of settings in which HPV vaccines may be administered to adolescents should increase. HPV vaccines should be available to adolescents in places where they interact with healthcare providers. Schools and pharmacies are two promising alternative settings for HPV vaccination in the United States.[10] Other settings may include health department clinics, urgent care centers, and emergency rooms. Survey results indicate that accessing HPV vaccines in alternative settings appealed to adolescent boys who had not had recent healthcare visits, as well as to their parents.[11,12] Given low vaccination rates among adolescent boys, strategies should be undertaken to reach this population more effectively.

Schools can educate adolescents and parents about the importance of vaccination and provide venues for vaccine administration. School-based programs have been extremely effective in other high-income countries, such as Australia, the United Kingdom, and Canada.[13-15] In the United States, school-based programs face challenges not encountered in these other countries. For example, decisions about whether to offer school-located vaccination in the U.S. generally are made by local superintendents and school boards. In addition, student populations often are covered by multiple healthcare payers, creating billing and reimbursement challenges. All of these factors point to the complexity of implementation and are the reasons why the Panel, which initially was inclined to recommend school-located vaccination programs, concluded that other approaches are more likely to be effective in the U.S., especially in the face of recent data regarding missed clinical opportunities.[16] Nevertheless, school-located vaccination programs may be feasible and effective for some populations in some settings (e.g., schools in which a large percentage of students are VFC- or Medicaid-eligible). Ongoing efforts to implement school-located programs (e.g., Health4Chicago program[17]) should be monitored and expanded, as appropriate. Furthermore, if vaccination rates in the U.S. do not improve dramatically over the next several years, the feasibility of school-located vaccination should be reexamined.

Pharmacies are another venue that could be utilized to increase HPV vaccination rates. Pharmacies are highly accessible to most people in the United States; about 275,000 licensed pharmacists practice in nearly 60,000 pharmacies across the country.[18,19] In health professional shortage and rural areas, pharmacists often are the most prevalent healthcare providers.[20] Other advantages of pharmacies include extended hours of operation (often including weekends) and availability of services without appointments. Pharmacists have played an important role in administering seasonal influenza and other vaccines in the United States. During the 2011-2012 flu season, 20 percent of U.S. adults who received flu vaccines received them in pharmacies.[21] Adolescents and their parents are open to having pharmacists provide adolescent vaccinations, including HPV vaccines.[11,12] Pharmacies also may be a place to reach young adults for catch-up vaccinations. However, in many states, pharmacists' authority to administer HPV vaccines is limited, precluding them from playing an active role in increasing HPV vaccination among primary target populations.

Objective 3.2: States should enact laws and implement policies that allow pharmacists to administer vaccines to adolescents, including younger adolescents.

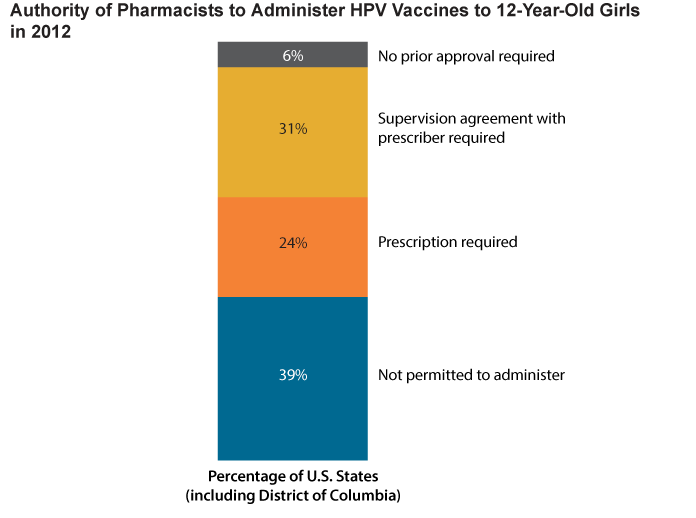

Pharmacists' authority to provide HPV vaccines to adolescents varies widely by state. A 2012 survey[22] of representatives of state pharmacy organizations in all 50 states and the District of Columbia found that pharmacists in more than one-third of states were not permitted to administer HPV vaccines to 12-year-old girls (Figure 7), though many of these states did allow pharmacists to provide the vaccine to women ages 19 and older. In states where pharmacists were allowed to administer the vaccine, mechanisms were highly variable. In the most permissive states, pharmacists could administer HPV vaccines to 12-year-old girls without prior approval from a prescriber,† while in other states pharmacists were required to sign supervision agreements with a specific prescriber or could vaccinate only individuals with a prescription.

States should adopt policies that allow pharmacists to deliver HPV vaccines to primary target populations (11- and 12-year-old boys and girls and others completing the three-dose series). Policies should be permissive enough to facilitate access to vaccination.

Figure 7

Source: Brewer NT, Chung JK, Baker HM, Rothholz MC, Smith JS. Pharmacist authority to provide HPV vaccine: novel partners in cervical cancer prevention. Gynecol Oncol. [Epub 2013 Dec 19]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24361732

Objective 3.3: Overcome remaining barriers to paying for HPV vaccines, including payment for vaccines provided outside the medical home and by out-of-network or nonphysician providers.

While HPV vaccines are among the most expensive in the United States (about $400 for the three-dose series),[23] their cost is covered for most age-eligible adolescents through private health insurance or public programs. Under provisions of the Affordable Care Act, all new group and individual health plans established or significantly changed since March 23, 2010, are required to cover HPV vaccination for both girls and boys without cost to patients.[24,25]‡ HPV vaccines also are available through VFC at no cost for eligible children under age 19 (there may be some cost for vaccine administration for children not covered by Medicaid).[26] Medicaid covers HPV vaccines for males and females 19 and 20 years of age through the Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment benefit.[27] Cost of HPV vaccines may be a barrier for uninsured young adults and for adolescents covered by older health plans not required to adhere to the law's requirements for vaccine coverage. These barriers should be addressed, although they are not the main reason for lagging HPV uptake.

Additional financial barriers may come into play, particularly for privately insured patients, if HPV vaccination becomes available in complementary settings and/or from additional provider types. The Affordable Care Act requires health insurers to cover all ACIP-recommended vaccinations at no cost to consumers when provided by in-network providers, which increases access of insured adolescents to HPV vaccines and other important preventive health services.[25] Cost may be a barrier, however, if privately insured adolescents obtain care from providers outside their networks. Patients covered by public programs (e.g., VFC, Medicaid) also must receive vaccines from recognized providers, although any provider authorized to prescribe vaccines under state law can become a VFC provider.[26] Pharmacists also can become VFC providers if granted authority to administer vaccines under state law.[28,29] These potential barriers should be addressed to ensure that they do not interfere with HPV vaccine uptake.

Footnotes

* In alignment with National Vaccine Advisory Committee recommendations, "venues outside the medical home" refer to settings complementary to the medical home that are shown to be appropriate and effective.

† In some of these states, a public official permitted use of his or her name on supervision agreements (e.g., standing orders, protocols, collaborative practice agreements).

‡ So-called grandfathered plans that were in place before the Affordable Care Act was implemented are not required to cover HPV vaccination. Plans lose this exempted status if they make significant changes in cost sharing, benefits, employer contributions, or access to coverage. In 2013, 36% of people who get health insurance through their jobs are enrolled in grandfathered plans. This is down from 48% in 2012 and 56% in 2011, and the number is expected to continue to decline as plans lose grandfathered status. Source: Kaiser Family Foundation and Health Research & Educational Trust. Employer health benefits: 2013 annual survey. Menlo Park (CA): KFF; 2013 Aug. Available from: http://kff.org/private-insurance/report/2013-employer-health-benefits/

References

- National Vaccine Advisory Committee. Update on the National Vaccine Advisory Committee standards for adult immunization practice. Washington (DC): NVAC; 2013 Sep 10. Available from: http://www.hhs.gov/nvpo/nvac/reports/nvacstandards.pdf

- American Academy of Pediatrics. The medical home. Pediatrics. 2002;110(1):184-6. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12093969

- American Academy of Family Physicians. Policies: immunizations [Internet]. Leawood (KS): AAFP; [cited 2013 Aug 20]. Available from: http://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/immunizations.html

- American College of Physicians. What is the patient-centered medical home? [Internet]. Philadelphia (PA): ACP; [cited 2013 Aug 19]. Available from: http://www.acponline.org/running_practice/delivery_and_payment_models/pcmh/understanding/what.htm

- Rand CM, Shone LP, Albertin C, Auinger P, Klein JD, Szilagyi PG. National health care visit patterns of adolescents: implications for delivery of new adolescent vaccines. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161(3):252-9. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17339506

- Irwin CE Jr, Adams SH, Park MJ, Newacheck PW. Preventive care for adolescents: few get visits and fewer get services. Pediatrics. 2009;123(4):e565-72. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19336348

- Dempsey AF, Freed GL. Health care utilization by adolescents on Medicaid: implications for delivering vaccines. Pediatrics. 2010;125(1):43-9. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19948567

- Elster A, Jarosik J, VanGeest J, Fleming M. Racial and ethnic disparities in health care for adolescents: a systematic review of the literature. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157(9):867-74. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12963591

- Newacheck PW, Hung YY, Park MJ, Brindis CD, Irwin CE Jr. Disparities in adolescent health and health care: does socioeconomic status matter? Health Serv Res. 2003;38(5):1235-52. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14596388

- Shah PD, Gilkey MB, Pepper JK, Gottlieb SL, Brewer NT. Promising alternative settings for HPV vaccination of U.S. adolescents. Expert Rev Vaccines. Forthcoming 2014.

- McRee AL, Reiter PL, Pepper JK, Brewer NT. Correlates of comfort with alternative settings for HPV vaccine delivery. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2013;9(2):306-13. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23291948

- Reiter PL, McRee AL, Pepper JK, Chantala K, Brewer NT. Improving human papillomavirus vaccine delivery: a national study of parents and their adolescent sons. J Adolesc Health. 2012;51(1):32-7. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22727074

- Gertig DM, Brotherton JM, Saville M. Measuring human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination coverage and the role of the National HPV Vaccination Program Register, Australia. Sex Health. 2011;8(2):171-8. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21592430

- Sheridan A, White J. Annual HPV vaccine coverage in England in 2009/2010. London (UK): Health Protection Agency, UK; 2010 Dec 22. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/147510/dh_123826.pdf.pdf

- Saraiya M, Steben M, Watson M, Markowitz L. Evolution of cervical cancer screening and prevention in United States and Canada: implications for public health practitioners and clinicians. Prev Med. 2013;57(5):426-33. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23402963

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Human papillomavirus vaccination coverage among adolescent girls, 2007-2012, and postlicensure vaccine safety monitoring, 2006-2013—United States. MMWR. 2013;62(29):591-5. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23884346

- Caskey RN, Macario E, Johnson DC, Hamlish T, Alexander KA. A school-located vaccination adolescent pilot initiative in Chicago: lessons learned. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2013;2(3):198-204. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24009983

- Klepser DG, Xu L, Ullrich F, Mueller KJ. Trends in community pharmacy counts and closures before and after the implementation of Medicare part D. J Rural Health. 2011;27(2):168-75. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21457309

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational outlook handbook, 2012-13 edition [Internet]. Washington (DC): U.S. Department of Labor; 2012 Mar 29 [cited 2013 Oct 27]. Available from: http://www.bls.gov/ooh/Healthcare/Pharmacists.htm#tab-1

- Knapp KK, Paavola FG, Maine LL, Sorofman B, Politzer RM. Availability of primary care providers and pharmacists in the United States. J Am Pharm Assoc (Wash). 1999;39(2):127-35. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10079647

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Flu vaccination coverage, National Flu Survey, March 2012: United States, 2011-2012 influenza season [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): CDC; [updated 2013 May 16; cited 2013 Aug 18]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/vaccination/nfs-survey-march2012.htm

- Brewer NT, Chung JK, Baker HM, Rothholz MC, Smith JS. Pharmacist authority to provide HPV vaccine: novel partners in cervical cancer prevention. Gynecol Oncol. [Epub 2013 Dec 19]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24361732

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC vaccine price list [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): CDC; [updated 2013 Jul 24; cited 2013 Jul 29]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/programs/vfc/awardees/vaccine-management/price-list/index.html

- Office of Adolescent Health. July 2012: don't forget! Vaccines for teens [Internet]. Rockville (MD): OAH; [updated 2013 Jul 19; cited 2013 Jul 29]. Available from: http://www.hhs.gov/ash/oah/news/e-updates/july-2012.html

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Affordable Care Act and immunization [Internet]. Washington (DC): DHHS; [updated 2012 Jan 20; cited 2013 Jul 29]. Available from: http://www.hhs.gov/healthcare/facts/factsheets/2010/09/The-Affordable-Care-Act-and-Immunization.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccines for Children Program (VFC) [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): CDC; [updated 2013 Apr 24; cited 2013 Jul 29]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/programs/vfc/index.html

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment [Internet]. Baltimore (MD): CMS; [cited 2013 Dec 10]. Available from: http://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Benefits/Early-and-Periodic-Screening-Diagnostic-and-Treatment.html

- Rothholz MC. System interventions to increase uptake of HPV vaccine: pharmacist perspective. Presented at: President's Cancer Panel meeting; 2012 Sep 13; Arlington, VA. Available from: http://deainfo.nci.nih.gov/advisory/pcp/pcpmeetings.htm

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. VFC healthcare providers information flyer [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): CDC; [updated 2012 Aug 31; cited 2013 Nov 14]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/programs/vfc/providers/questions/qa-flyer-hcp.html