- Home

- Letter to President Obama

- Acknowledgements

- Executive Summary

- Preface

- Part 1: The Case for HPV Vaccination

- Part 2: Urgency for Action

- Part 3: Accelerating HPV Vaccine Uptake in the U.S.

- Goal 1: Reduce Missed Clinical Opportunities

- Goal 2: Increase Acceptance of HPV Vaccines

- Goal 3: Maximize Access to HPV Vaccination Services

- Part 4: Increasing Global HPV Vaccination

- Part 5: High-Priority Research

- Conclusions

- Appendices

- Acronyms

Goal 1: Reduce Missed Clinical Opportunities to Recommend and Administer HPV Vaccines

According to a recent report from CDC, missed clinical opportunities are the most important reason why the U.S. has not achieved high rates of HPV vaccine uptake.[1] Many vaccine-eligible adolescents do not receive HPV vaccines during visits with their healthcare providers. One survey of parents of 11- to 17-year-old boys and girls found that among those who had not received HPV vaccines, 84 percent of boys and 79 percent of girls had had preventive care visits within the past 12 months.[2] Many times, adolescents received other recommended vaccines at these visits but did not receive HPV vaccines. One report suggests that as many as two-thirds of 11- and 12-year-old vaccine-eligible girls may not be receiving HPV vaccines at visits at which they receive at least one other vaccine.[3]

Factors Contributing to Providers' Hesitancy

- Limited understanding of HPV-associated diseases and benefits of HPV vaccination, particularly for males

- Concerns about safety

- Concerns about inadequate reimbursement for vaccines

- Personal attitudes and beliefs

- Discomfort talking to parents and adolescents about a topic related to sexual behavior

- Concerns about parental resistance

- Preference for vaccinating older versus younger adolescents

- Lack of time or incentives to educate parents and patients about HPV and HPV vaccines

- Lack of systems to remind providers to offer vaccines to age-eligible patients

Several factors contribute to providers' hesitancy in recommending HPV vaccines (see Factors Contributing to Providers' Hesitancy).[4-13] Efforts should be made to address barriers of importance to different kinds of providers. Doing so could substantially reduce the number of missed opportunities to recommend and administer HPV vaccines. Evidence from other cancer prevention areas, such as avoiding or stopping tobacco use, as well as increasing uptake of other vaccines, indicates that concerted efforts to reduce missed clinical opportunities can change physician behaviors.[14-17]

There is every reason to believe that those lessons are relevant to HPV vaccination.

However, substantial changes in healthcare rarely occur because of minor modifications in one or two facets of systems. Lessons from the past few decades of provider interventions demonstrate that multiple kinds of interventions usually are needed.

Objective 1.1: CDC should develop, test, disseminate, and evaluate the impact of integrated, comprehensive communication strategies for physicians and other relevant health professionals.

Objective 1.2: Providers should strongly encourage HPV vaccination of age-eligible males and females whenever other vaccines are administered.

Objective 1.3: Healthcare organizations and practices should use electronic office systems, including electronic health records (EHRs) and immunization information systems (IIS), to avoid missed opportunities for HPV vaccination.

Objective 1.4: Healthcare payers should reimburse providers adequately for HPV vaccines and for vaccine administration and services.

Objective 1.5: The current Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) quality measure for HPV vaccination of adolescent females should be expanded to include males.

Objective 1.6: Create a Healthy People 2020 HPV vaccination goal for males.

Objective 1.1: CDC should develop, test, disseminate, and evaluate the impact of integrated, comprehensive communication strategies for physicians and other relevant health professionals.

Physicians and other healthcare providers should be knowledgeable about HPV infections and associated diseases, protection conferred by HPV vaccines, and safety of these vaccines. They also need tools and strategies to help them communicate with parents and other caregivers about a topic that makes some providers uncomfortable. A multipronged, comprehensive communications strategy is essential to accomplish this. CDC is the logical choice to lead this effort but will require additional funding to do so. Funding should be allocated for design, implementation, and evaluation of sustained communications efforts.

Strategies should be based on evidence and communications best practices.[18] Messages should:

- Focus on HPV vaccines as a tool to prevent multiple cancers.

- Emphasize the importance of vaccinating both males and females.

- Emphasize the importance of vaccinating the primary target age group (11- to 12-year-olds).

- Promote catch-up vaccination for older adolescents and young adults, as needed.*

- Reinforce HPV vaccine efficacy and safety.

- Encourage administration of HPV vaccines as part of an adolescent vaccine platform. Unless contraindicated, HPV vaccines should be administered at the same time as other adolescent vaccines.

The many other stakeholders in the HPV vaccine arena also should collaborate to increase provider understanding and acceptance of HPV vaccines. Mutually reinforcing messages from key organizations will contribute to greater impact than if organizations continue to communicate their individual, nuanced messages. Professional societies and other organizations also should advocate strongly for HPV vaccine use and support their members in increasing uptake.

Objective 1.2: Providers should strongly encourage HPV vaccination of age-eligible males and females whenever other vaccines are administered.

High coverage rates for other adolescent vaccines (see Part 2) make it clear that widespread HPV vaccination is possible in the United States. Nearly 85 percent of adolescents received Tdap vaccines in 2012, but only about half of girls and 20 percent of boys received their first HPV vaccine doses.[19] Adolescents are being vaccinated, but all too often they are not being vaccinated against HPV.

92.6% of 13- to 17-year-old U.S. girls would have received at least their first HPV vaccine dose by 2012 if all missed opportunities for HPV vaccination had been eliminated.

The Panel cannot overemphasize the role of providers in overcoming disparities in uptake between HPV and other adolescent vaccines. Physicians' recommendation for HPV vaccines to parents and other caregivers is the strongest predictor of HPV vaccination among adolescents.[20,21] When physicians and other providers recommend HPV vaccination, most parents and adolescents comply.[22]

However, surveys of both providers and parents indicate that providers frequently fail to recommend HPV vaccines for age-eligible adolescents.[1,23,24] Each time this occurs, there is a missed opportunity to prevent cancer. A recent CDC analysis indicated that if all missed opportunities† for HPV vaccination had been eliminated between the time the ACIP HPV vaccination recommendation was published in 2007 and 2012, 92.6 percent of 13- to 17-year-old U.S. girls would have received at least their first HPV vaccine dose in or before 2012.[1]

The Panel recommends in the strongest possible terms that physicians administer HPV vaccines along with other recommended vaccines. This strategy will reduce physicians' and parents' discomfort. Moreover, it will place HPV vaccines where they should be—as essential parts of the adolescent vaccine platform.

Objective 1.3: Healthcare organizations and practices should use electronic office systems, including electronic health records (EHRs) and immunization information systems (IIS), to avoid missed opportunities for HPV vaccination.

Physician surveys indicate that lack of standard office procedures may contribute to low rates of HPV vaccine recommendation and uptake.[4,25] Use of provider reminders improves vaccination coverage in children, adolescents, and adults.[26] Many techniques are useful for delivering reminders (e.g., notes prepared in advance and posted in client charts). The increasing presence of technology in clinical settings offers new tools to reduce missed opportunities for HPV vaccination.

"Meaningful use" refers to the set of standards defined by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Incentive Programs that allows eligible providers and hospitals to earn incentive payments by meeting specific criteria.

Electronic health record use has increased dramatically among physicians, other providers, and hospitals over the past few years, driven in large part by incentives created by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA, P.L. 111-5). As of April 2013, more than half of eligible health professionals (mostly physicians) and 80 percent of eligible hospitals had demonstrated meaningful use of EHRs (see sidebar), up from 17 and 9 percent, respectively, in 2008.[27] Reminders for initiation and completion of HPV vaccine series should be integrated into EHR systems. These reminders will ensure that providers recommend the vaccine to patients during office visits and facilitate follow-up for subsequent doses.

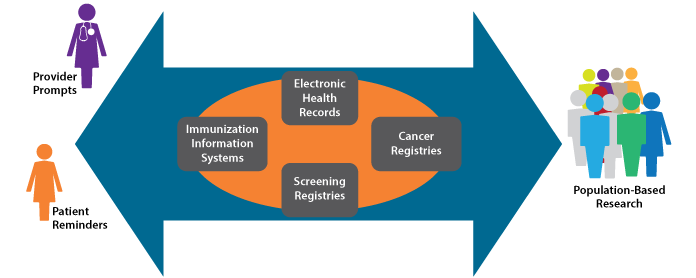

Expanded EHR use also may facilitate delivery of reminders to parents (including those delivered via mobile devices, email, text messaging, and other technologies) informing them that their children are due or overdue for an HPV vaccine dose. Like provider reminders, patient reminder and recall systems are effective for increasing vaccination rates.[28,29] However, reminder and recall systems are underused by pediatricians and other providers.[30,31] Robust centralized immunization information systems that are interoperable and integrated with office-based EHRs could make it easier to implement reminders/recalls. In addition to supporting clinical practice, IIS enable vaccine uptake monitoring and can facilitate study of vaccination impact (see Health Information Technology and HPV Vaccination).

Health Information Technology and HPV Vaccination

Health information technology (IT) is playing an increasingly important role in healthcare delivery and research. The Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act, enacted as part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, included $19 billion for promotion of health information technology adoption in the United States. Increased use of health IT, driven in part by this investment, has important implications for public health.

Of particular importance to HPV vaccination efforts are improvements in immunization information systems (IIS). IIS are confidential, computerized, population-based systems that collect and consolidate vaccination data within a geographic area (often a state). IIS data can be used to help ensure that individuals receive recommended vaccines (e.g., through use of reminder/recall systems), but also can support vaccination program planning and research. In the U.S., 84 percent of children under 6 years old are included in IIS, but coverage of adolescents is only 53 percent. It should be noted, however, that some state IIS have achieved over 95 percent coverage of both age groups. Efforts to increase IIS coverage of adolescents should be maintained and increased to enable monitoring and improvement of HPV vaccination.

The keys to optimizing the return on investment in health IT are interoperability and integration. Linkages between EHRs, IIS, and other systems would provide unprecedented opportunity for population-based monitoring and research. In the case of HPV vaccines, linkages among IIS and screening or cancer registries would enable study of the impact of HPV vaccination, including differences in rates of HPV-associated precancers and cancers between vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals. Among other things, this information could be used to inform modification of cancer screening guidelines.

Highly integrated systems are possible, but their development requires cooperation of many stakeholders and significant investment of time and resources. Such cooperation and investment should be encouraged. In instances where system linkages have been achieved, important information already is being generated. For example, the continuum of cervical cancer prevention is monitored in New Mexico through linkage of a population-based cervical cancer screening registry (the only one of its kind in the United States) and HPV vaccine administrative data. These data will be used to inform integration of cervical cancer screening and HPV vaccination.

Sources:

Community Preventive Services Task Force. The Guide to Community Preventive Services. Increasing appropriate vaccination: immunization information systems [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): the Task Force; 2011 Apr 18 [cited 2013 Aug 17]. Available from: http://www.thecommunityguide.org/vaccines/RRimminfosystems.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Immunization information systems (IIS): 2011 IISAR data participation rates [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): CDC; [updated 2013 Apr 11; cited 2013 Aug 23]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/programs/iis/annual-report-IISAR/2011-data.html#child

University of New Mexico School of Medicine. NMHPVPR: the New Mexico HPV Pap Registry [Internet]. Albequerque (NM): UNM; [cited 2013 Aug 20]. Available from: http://hpvprevention.unm.edu/NMHPVPR/

Integrated Health IT Supports Clinical Care and Research

Objective 1.4: Healthcare payers should reimburse providers adequately for HPV vaccines and for vaccine administration and services.

Vaccines for Children Program

VFC is a federal entitlement program that provides immunizations at little or no cost to children who might not be vaccinated because of inability to pay. Children younger than 19 years of age are eligible for VFC if they are Medicaid-eligible, American Indian or Alaska Native, uninsured, and/or their insurance does not cover recommended vaccines.

In 2010, an estimated 82 million VFC vaccine doses were administered to approximately 40 million children.

Sources: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of the Inspector General. Vaccines for Children program: vulnerabilities in vaccine management. Washington (DC): DHHS; 2012 Jun. Available from: http://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-04-10-00430.pdf

Costs for vaccine administration are reimbursed separately. In the case of VFC-provided vaccines, administration costs are reimbursed through Medicaid or paid by patients/parents. For privately insured patients, administration costs are reimbursed by insurance companies.

Inadequate provider reimbursement creates disincentives for strong HPV vaccination recommendations.

Up-front costs of purchasing HPV vaccines have been cited as a significant barrier to HPV vaccination in numerous provider surveys.[4-6,24,35-37] In some cases, concerns about cost may lead practices to decide not to stock HPV vaccines.[35,36] Inadequate reimbursement for vaccine administration costs also creates disincentives for strong provider recommendations for HPV vaccination. Reimbursement for vaccine administration by private insurers varies widely and often does not cover provider costs, particularly if only one vaccine is given during a visit.[32,38] This is another reason why integrating HPV vaccines into the adolescent platform is appropriate.

Low levels of reimbursement for vaccine administration by Medicaid (including for vaccines administered through VFC) have been an area of concern for several years.[32] The Affordable Care Act (P.L. 111-148) increased reimbursement for vaccines administered through Medicaid for the first time in nearly 20 years.[39,40] This change, which applies to 2013 and 2014, is laudable and should be extended. The Panel encourages modification of federal laws and regulations as necessary to ensure adequate Medicaid reimbursement for vaccine administration in 2015 and beyond.

Continued monitoring is needed to ensure that vaccine financing issues do not limit access to HPV or other vaccines. At a minimum, payers should reimburse direct and indirect costs associated with purchasing and maintaining inventories of recommended vaccines.[41] Also, reimbursement for vaccine administration by private payers and Medicaid should be at least equal to reimbursement provided through Medicare.

Objective 1.5: The current Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) quality measure for HPV vaccination of adolescent females should be expanded to include males.

HEDIS is a set of standardized measures related to healthcare and services.[42] More than 90 percent of U.S. health plans use HEDIS to measure performance. Accreditation by the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) depends in large part on how well health plans perform with respect to these measures. In addition, health plan purchasers often use HEDIS data when selecting plans. Plans have an incentive to change practices and make improvements to optimize their HEDIS scores.

In 2012, a HEDIS measure was created to assess the percentage of female adolescents 13 years of age who had had three doses of HPV vaccine by their thirteenth birthdays.[43] After two years of testing, the measure recently was approved by the NCQA Committee on Performance and will be included as a publicly reported HEDIS measure in 2014.[44] The Panel commends adoption of this measure. It likely will promote HPV vaccine uptake among girls. However, it does not address vaccination of boys, who also are at risk of HPV-associated diseases, including cancer. NCQA should expand the HEDIS measure on HPV vaccination to include adolescent boys.

Objective 1.6: Create a Healthy People 2020 HPV vaccination goal for males.

The Healthy People initiative provides science-based, 10-year national objectives for improving the health of the U.S. population. These objectives are used by federal, state, and local health and public health programs and others to inform prioritization and planning processes.

Current Healthy People 2020 objectives include increasing HPV vaccine completion rates for females ages 13 to 15 years to 80 percent.[45] Healthy People 2020 objectives should be updated to include an HPV vaccination goal for males equivalent to that for females. This is consistent with ACIP's 2011 recommendation for HPV vaccination of adolescent males.

Footnotes

* The Panel supports the actions of CDC and other federal agencies to focus especially on adolescents ages 11-12 years as the ideal target group for HPV vaccination. However, the catch-up period for adolescents and young adults not previously vaccinated is also an important window for cancer prevention. If failure to vaccinate 11- to 12-year-olds is the first missed opportunity, failure to vaccinate young women ages 13-26 who were not previously vaccinated or did not complete the three-dose series and males ages 13-21 is an additional missed opportunity.

† For this analysis, a missed opportunity was defined as a healthcare encounter occurring on or after a girl's 11th birthday and on or after March 23, 2007 (publication date of ACIP's initial recommendation for HPV vaccination of girls) during which a girl received at least one vaccine but did not receive the HPV vaccine.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Human papillomavirus vaccination coverage among adolescent girls, 2007-2012, and postlicensure vaccine safety monitoring, 2006-2013—United States. MMWR. 2013;62(29):591-5. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23884346

- Gilkey MB, Moss JL, McRee AL, Brewer NT. Do correlates of HPV vaccine initiation differ between adolescent boys and girls? Vaccine. 2012;30(41):5928-34. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22841973

- Stokley S, Cohn A, Jain N, McCauley MM. Compliance with recommendations and opportunities for vaccination at ages 11 to 12 years: evaluation of the 2009 national immunization survey-teen. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165(9):813-8. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21893647

- Quinn GP, Murphy D, Malo TL, Christie J, Vadaparampil ST. A national survey about human papillomavirus vaccination: what we didn't ask, but physicians wanted us to know. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2012;25(4):254-8. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22516792

- Vadaparampil ST, Murphy D, Rodriguez M, Malo TL, Quinn GP. Qualitative responses to a national physician survey on HPV vaccination. Vaccine. 2013;31(18):2267-72. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23499608

- Daley MF, Crane LA, Markowitz LE, Black SR, Beaty BL, Barrow J, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination practices: a survey of U.S. physicians 18 months after licensure. Pediatrics. 2010;126(3):425-33. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20679306

- Perkins RB, Clark JA. What affects human papillomavirus vaccination rates? A qualitative analysis of providers' perceptions. Womens Health Issues. 2012;22(4):e379-86. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22609253

- McCave EL. Influential factors in HPV vaccination uptake among providers in four states. J Community Health. 2010;35(6):645-52. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20336354

- Perkins RB, Clark JA. Providers' attitudes toward human papillomavirus vaccination in young men: challenges for implementation of 2011 recommendations. Am J Mens Health. 2012;6(4):320-3. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22398992

- Yarnall KS, Pollak KI, Ostbye T, Krause KM, Michener JL. Primary care: is there enough time for prevention? Am J Public Health. 2003;93(4):635-41. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12660210

- Solberg LI, Nordin JD, Bryant TL, Kristensen AH, Maloney SK. Clinical preventive services for adolescents. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37(5):445-54. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19840701

- Yarnall KS, Ostbye T, Krause KM, Pollak KI, Gradison M, Michener JL. Family physicians as team leaders: "time" to share the care. Prev Chronic Dis. 2009;6(2):A59. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19289002

- Holman DM, Benard V, Roland KB, Watson M, Liddon N, Stokley S. Barriers to human papillomavirus vaccination among U.S. adolescents: a systematic review of the literature. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(1):76-82. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24276343

- Community Preventive Services Task Force. The guide to community preventive services. Increasing appropriate vaccination [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): the Task Force; [updated 2013 Aug 5; cited 2013 Sep 14]. Available from: http://www.thecommunityguide.org/vaccines/index.html

- Fiore MC, Fleming MF, Burns ME. Tobacco and alcohol abuse: clinical opportunities for effective intervention. Proc Assoc Am Physicians. 1999;111(2):131-40. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10220808

- Davis D, Galbraith R. Continuing medical education effect on practice performance: effectiveness of continuing medical education: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Educational Guidelines. Chest. 2009;135(3 Suppl):42S-8S. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19265075

- Aspy CB, Mold JW, Thompson DM, Blondell RD, Landers PS, Reilly KE, et al. Integrating screening and interventions for unhealthy behaviors into primary care practices. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(5 Suppl):S373-80. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18929984

- World Health Organization. HPV vaccine communication: special considerations for a unique vaccine. Geneva (CH): WHO; 2013. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/94549/1/WHO_IVB_13.12_eng.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National and state vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13-17 years—United States, 2012. MMWR. 2013;62(34):685-93. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23985496

- Reiter PL, McRee AL, Pepper JK, Gilkey MB, Galbraith KV, Brewer NT. Longitudinal predictors of human papillomavirus vaccination among a national sample of adolescent males. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(8):1419-27. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23763402

- Gargano LM, Herbert NL, Painter JE, Sales JM, Morfaw C, Rask K, et al. Impact of a physician recommendation and parental immunization attitudes on receipt or intention to receive adolescent vaccines. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2013;9(12):2627-33. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23883781

- Dorell CG, Yankey D, Santibanez TA, Markowitz LE. Human papillomavirus vaccination series initiation and completion, 2008-2009. Pediatrics. 2011;128(5):830-9. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22007006

- Reiter PL, Gilkey MB, Brewer NT. HPV vaccination among adolescent males: results from the National Immunization Survey-Teen. Vaccine. 2013;31(26):2816-21. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23602667

- Vadaparampil ST, Kahn JA, Salmon D, Lee JH, Quinn GP, Roetzheim R, et al. Missed clinical opportunities: provider recommendations for HPV vaccination for 11-12 year old girls are limited. Vaccine. 2011;29(47):8634-41. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21924315

- Kahn JA, Rosenthal SL, Tissot AM, Bernstein DI, Wetzel C, Zimet GD. Factors influencing pediatricians' intention to recommend human papillomavirus vaccines. Ambul Pediatr. 2007;7(5):367-73. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17870645

- Community Preventive Services Task Force. The guide to community preventive services. Increasing appropriate vaccination: provider reminders [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): the Task Force; 2008 Jun [updated 2013 Jul 8; cited 2013 Aug 17]. Available from: http://www.thecommunityguide.org/vaccines/providerreminder.html

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Doctors and hospitals' use of health IT more than doubles since 2012 [News Release]. Washington (DC): DHHS; 2013 May 2 [cited 2013 Aug 17]. Available from: http://www.hhs.gov/news/press/2013pres/05/20130522a.html

- Briss PA, Rodewald LE, Hinman AR, Shefer AM, Strikas RA, Bernier RR, et al. Reviews of evidence regarding interventions to improve vaccination coverage in children, adolescents, and adults. The Task Force on Community Preventive Services. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18(1 Suppl):97-140. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10806982

- Jacobson Vann JC, Szilagyi P. Patient reminder and patient recall systems to improve immunization rates. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005(3):CD003941. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16034918

- Tierney CD, Yusuf H, McMahon SR, Rusinak D, O' Brien MA, Massoudi MS, et al. Adoption of reminder and recall messages for immunizations by pediatricians and public health clinics. Pediatrics. 2003;112(5):1076-82. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14595049

- Pereira JA, Quach S, Heidebrecht CL, Quan SD, Kolbe F, Finkelstein M, et al. Barriers to the use of reminder/recall interventions for immunizations: a systematic review. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2012;12:145. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23245381

- Lindley M, Orenstein W, Shen A, Rodewald L, Birkhead G. Assuring vaccination of children and adolescents without financial barriers: recommendations from the National Vaccine Advisory Committee (NVAC). Washington (DC): U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2009 Mar 2. Available from: http://www.hhs.gov/nvpo/nvac/nvacfwgreport.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccines for Children Program (VFC) [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): CDC; [updated 2013 Apr 24; cited 2013 Jul 29]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/programs/vfc/index.html

- Dempsey AF, Davis MM. Overcoming barriers to adherence to HPV vaccination recommendations. Am J Manag Care. 2006;12(17 Suppl):S484-91. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17203992

- Gottlieb SL, Brewer NT, Smith JS, Keating KM, Markowitz LE. Availability of human papillomavirus vaccine at medical practices in an area with elevated rates of cervical cancer. J Adolesc Health. 2009;45(5):438-44. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19837349

- Young JL, Bernheim RG, Korte JE, Stoler MH, Guterbock TM, Rice LW. Human papillomavirus vaccination recommendation may be linked to reimbursement: a survey of Virginia family practitioners and gynecologists. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2011;24(6):380-5. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21906978

- Keating KM, Brewer NT, Gottlieb SL, Liddon N, Ludema C, Smith JS. Potential barriers to HPV vaccine provision among medical practices in an area with high rates of cervical cancer. J Adolesc Health. 2008;43(4 Suppl):S61-7. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18809147

- Freed GL, Cowan AE, Gregory S, Clark SJ. Variation in provider vaccine purchase prices and payer reimbursement. Pediatrics. 2009;124(5 Suppl):S459-65. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19948577

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicaid program; payments for services furnished by certain primary care physicians and charges for vaccine administration under the Vaccines for Children Program; Correction. Fed Regist. 2012 Dec 14;77(241):74381-2. Available from: https://www.federalregister.gov/articles/2012/12/14/2012-29640/medicaid-program-payments-for-services-furnished-by-certain-primary-care-physicians-and-charges-for

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicaid program; payments for services furnished by certain primary care physicians and charges for vaccine administration under the Vaccines for Children Program. Fed Regist. 2012 May 11;77(92):27671-91. Available from: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2012-05-11/html/2012-11421.htm

- American Academy of Pediatrics. The business case for pricing vaccines. Elk Grove Village (IL): AAP; 2012 Mar. Available from: http://www2.aap.org/immunization/pediatricians/pdf/TheBusinessCase.pdf

- National Committee for Quality Assurance. HEDIS and performance measurement [Internet]. Washington (DC): NCQA; [cited 2013 Aug 17]. Available from: http://www.ncqa.org/HEDISQualityMeasurement.aspx

- National Committee for Quality Assurance. HEDIS® 2012. Healthcare Effectiveness Data & Information Set. Vol. 2, Technical specifications for health plans. Washington (DC): NCQA; 2011.

- National Committee for Quality Assurance. HEDIS® 2014. Healthcare Effectiveness Data & Information Set. Vol. 2, Technical specifications update. Washington (DC): NCQA; 2013 Sep 30. Available from: http://www.ncqa.org/Portals/0/HEDISQM/HEDIS2014/HEDIS_2014_Volume_2_Technical_Update_FINAL_9.30.13.pdf

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2020 topics and objectives: immunization and infectious diseases objectives [Internet]. Washington (DC): DHHS; [updated 2013 Apr 24; cited 2013 Jul 26]. Available from: http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/objectiveslist.aspx?topicId=23